For years Richmond City Councilmember Cesar Zepeda has been on an unsuccessful crusade to persuade the grocery store chains of America — or at least one of them — to bring a supermarket back to his industrial city on the edge of the San Francisco Bay.

He’s persistent. He’s called corporate headquarters. He’s emailed customer relations. Occasionally, he’s gotten executives on the phone, and listened to them stammer on about why Richmond isn’t the right place for them to locate a store, despite its population of 117,000 in the heart of the Bay Area.

After years of disappointing conversations, Zepeda has concluded something basic about his city: It is paying a big price by not being able to tell its own story.

Richmond has not had its own daily newspaper for years. The loss came during a period of profound struggles for the town, which has dealt with fluctuating crime, economic problems and environmental challenges. Zepeda and others say there is a lot of good and bad going on in Richmond, but the dearth of local news coverage offers a skewed view of the city — oversimplified and years out of date — as an impoverished and violent community.

“The lack of coverage puts us into deserts of everything. We have a hospital desert. We have a grocery store desert,” Zepeda said. “Just the lack of any coverage, it affects the perception.”

In this news desert, the main information source has been the Richmond Standard, a news website funded by Chevron, Richmond’s largest employer. It offers reports on youth sports, crime logs and things to do in town. Recent articles have highlighted a mural project, a car caravan supporting racial justice and upcoming closures to Interstate 80.

But the Standard is conspicuously silent when it comes to hard-hitting reporting on the Chevron refinery, which activists blame for the city’s high rates of hospitalization for childhood asthma. On June 19, the City Council voted to put a measure on the November ballot asking local voters to levy a tax on the refinery that would generate tens of millions of dollars a year to be used as the city sees fit. The lead-up and follow-up to this hugely consequential development were nowhere on the Standard’s homepage.

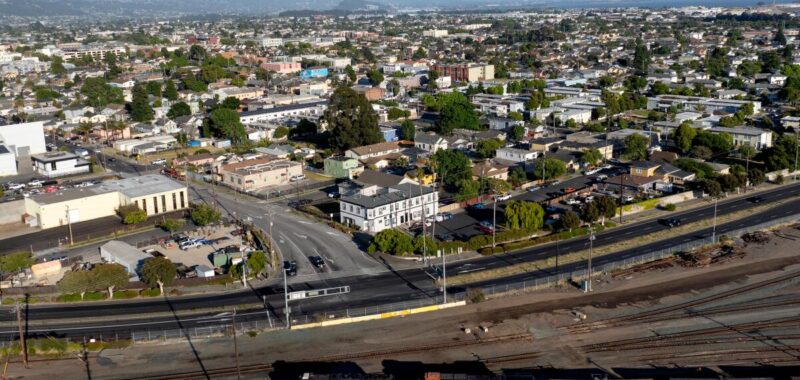

Richmond is one in a swelling number of California communities that in recent years have had to navigate civic life without a traditional newspaper. The city — a onetime shipbuilding hub that fell on hard times and is now in the midst of a rebound — was once served by multiple papers, but the grim economics took them out one by one.

All the while, in-depth daily coverage of Richmond, a city with 23 distinct neighborhoods and cutthroat politics, with a refinery of vital importance to the state’s energy economy, shrank and shrank.

The issue of California’s growing news deserts — and the fallout on civic engagement — has become a heated topic in the state Legislature, where Assemblymember Buffy Wicks (D-Oakland) is pushing a measure, Assembly Bill 886, that would require leading social media platforms and search engines to pay news outlets for accessing their articles, either through a predetermined fee or through an amount set by arbitration. Publishers would have to use 70% of those funds to pay journalists in California. Lawmakers are also considering state Senate Bill 1327, which would tax large tech platforms for the data they collect from users and pump the money into news organizations by giving them a tax credit for employing full-time journalists.

AB 886 is sponsored by the California News Publishers Assn., whose members have argued for years that online search engines and social media platforms are gutting the newspaper business by gobbling up advertising revenue while publishing content they don’t pay for. (The Los Angeles Times is a CNPA member, and its business leaders have publicly supported the measure.)

The legislation has drawn staunch opposition from Google and other tech companies, which contend it would upend their business model.

The rise of the search engine is one of many factors pushing California newspapers out of business. Richmond’s news decline began well before eyeballs and advertising migrated online.

But Richmond’s story is not just about the loss of news. It also shows how a community gets information in a post-newspaper world.

Richmond is now a laboratory for online journalism startups, including the one owned by Chevron, whose massive refinery looms over the city and has been the focus of ongoing concerns over toxic emissions.

The region’s independent online publications are sometimes hard-hitting and admirably hardworking, but they are limited in size and reach. The students at UC Berkeley’s journalism school operate Richmond Confidential, a news lab for student reporters that is funded by a grant from the Ford Foundation. Since late 2020, the husband-and-wife team of Linda and Soren Hemmila have put out the Grandview Independent, whose website proclaims: “For us, there is no story too small.”

There is also a youth-focused site, the Pulse, and a publication that focuses on the area’s Black community. In late June, the team behind the well-regarded local news websites Berkeleyside and Oaklandside launched a sister publication called Richmondside.

Still, said City Councilmember Doria Robinson, “the unfortunate best source” for much of the day-to-day goings on in recent years has been the Richmond Standard.

Robinson is a third-generation Richmond resident who was elected to the council in 2022 and for years before that ran a nonprofit farm in North Richmond. She said she is grateful for the work of all the reporters laboring on a shoestring to bring news to her city. But it doesn’t replace the weight and influence of the local paper she remembers from her youth.

And as for the Chevron paper, she said: “It is just unfortunate to have to depend on a project that is openly and proudly funded by our local petroleum [company].”

In 2011, the news group that owned the West County Times made an announcement that had become all too familiar to Richmond readers: More layoffs and cuts were coming to the chain that published the West County Times along with several other outlets in the East Bay. There would be less news out of Richmond.

Former Councilmember Tom Butt, who sends out an email about Richmond that doubles as an informal newsletter, lamented the decision and urged citizens to complain, writing: “What will this mean for Richmond? Undoubtedly, it will mean reduced coverage of local news.”

Five years later, in 2016, the ax swung again, and the West County Times was merged, along with a number of other newspapers, into two. Another chunk of the reporting staff was cut.

“The level of connection we were able to maintain with people in the community really evaporated in a significant way,” said Craig Lazzeretti, a journalist who covered the region for 30 years, much of it in Richmond. Over time, Richmond lost its education and public safety reporters, he said, and while City Hall remained a priority, coverage of sports and entertainment also declined.

In its heyday, the coverage was rigorous, and “it did play a significant role” in civic life, Lazzeretti said. “You had a lot of strong political personalities in Richmond.”

He admits the local newspapers of that era were not perfect: “We were covering an ethnically diverse city, and there wasn’t a lot of ethnic diversity in our newsroom.” But reporters did try to reflect what was going on in the city.

As the 21st century dawned, the West County Times, the lone paper still covering Richmond vigorously, was facing a menacing economic shift: the rise of the internet. Advertising dollars — long the financial mainstay of traditional newspapers — moved online, budgets dwindled, and soon there were almost no reporters left to cover Richmond on a daily basis.

Meanwhile, life in Richmond was entering a dark period. The city’s better-paying manufacturing and industrial jobs were evaporating because of economic shifts, spawning an exodus of middle-class earners to the suburbs.

Chevron, which had long been one of the biggest influences on local politics, stayed. But as concerns mounted about the effects of its refinery on air quality, progressive candidates began organizing to counter the weight of the oil company.

By 2010, candidates backed by the Richmond Progressive Alliance had pressed the company to contribute more fees to the city to compensate for environmental damage. And then came the disaster of August 2012, when a corroded pipe at the refinery sprung a leak, igniting a series of fiery explosions that shrouded the East Bay in choking black smoke. More than 100,000 people were ordered to shelter in place, with windows and doors sealed shut, and thousands sought medical treatment after inhaling toxic air.

The episode set off a wave of activism that included investigations into Chevron’s operating practices. In August 2013, Chevron agreed to plead no contest to criminal charges stemming from the fire and pay $2 million in fines.

Five months later, on Jan. 23, 2014, Chevron launched the Standard.

“We think it’s good for us to have a conversation with Richmond on important issues, and we also think there are a lot of good stories in this city that don’t get told every day,” the company wrote to readers in announcing the news site.

Progressives were alarmed: The entity that in their eyes most needed watchdogging was now a leading source of local coverage.

Still there was now a reporter roaming the neighborhoods, reporting on a new baseball field, a burglary, local businesses and even some local politics.

In June, while the Standard ignored the City Council’s vote on taxing the refinery, it did cover a Little League triumph, a shooting that left two people dead and the schedule of movies to be screened this summer at “Movies in the Park.”

Ross Allen, a spokesperson for Chevron, said the community didn’t need the Standard to cover the council’s vote — it was a big enough event that it received ample coverage in mainstream California publications.

He added, however, that Chevron opposes the proposed tax, and that “we will have coverage on the reasons why that is a terrible idea for Richmond in the Standard. We’ll have it everywhere.”

The Times interviewed Richmond residents in June to gauge whether the long absence of a local newspaper mattered in their lives. Many said they were unaware of Richmond’s news media history, but in interview after interview stressed their hunger for news about their city.

Juan Alfredo, 27, recently moved to Richmond from Guatemala after a stopover in Los Angeles. He paused to chat while walking his little white poodle in the city’s Miller/Knox Regional Shoreline Park. Across the sparkling waters of the bay, the San Francisco skyline and misty green hills of Marin County rose in the distance.

Alfredo said that he loves Richmond’s physical beauty, but that his new home struggles with some quality-of-life issues, including trash and messed-up streets. And he has no idea where to turn for information about what is going on in the city.

A few miles away, Elaina Jones, who moved from nearby Orinda last year, said she enjoys the community in the Marina Bay neighborhood. But she said she has little sense of what’s happening in the rest of the city. What she does know, she learns not from local media but from talking to her older neighbors.

Still, she plans to vote in the local elections in November — and said to do so she needs to figure out what’s going on.

One of her would-be representatives, City Council candidate Sue Wilson, said the lack of a local newspaper means candidates often work to reach voters one-on-one, by going to their doors.

Lots of residents are in the dark about who’s running for office and their positions on issues. That may be one reason, some officials said, that voter turnout in local elections is abysmal.

Wilson said Richmond’s tumultuous politics often make her think, “This seems like the sort of thing that would be in the newspaper.”

She paused. “But then there is no newspaper.”

The journalists at Richmondside hope to do their part to change that. On June 25, the site went live with what they hope will be dynamic coverage.

Richmondside is the latest offshoot of the Cityside Journalism Initiative, a nonprofit online news platform launched by journalists looking to reinvigorate local news coverage in the Bay Area. The effort is funded through grants and reader donations.

Richmondside’s new editor, Kari Hulac, said the publication would have two full-time staffers and two interns, as well as editorial support from across the organization and contributions from freelancers. She said readers can look forward to air quality coverage, as well as stories on neighborhood issues, small businesses and public safety.

For Hulac, a veteran Bay Area journalist, the launch represents a welcome second chance to be involved in local news.

“I’ve locked the door on a newsroom,” she recalled of shutting a news bureau in Tracy. “I put the handwritten note on the door: ‘This office is closed permanently.’”

“If you had told me, I don’t know, a year ago, that I would be back in the Bay Area working in a local newsroom again, I never in a million years would have believed it,” she said.