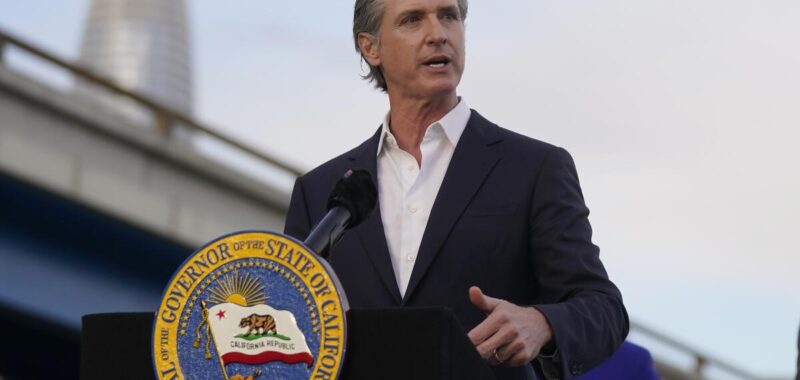

It’s becoming increasingly clear in Sacramento: The administration of Gov. Gavin Newsom is intent on pumping up state power to oversee the slow decline of California’s gasoline refinery industry.

It remains to be seen whether the state Legislature will go along.

Newsom called a special legislative session to address gasoline price spikes, such as the one last year that sent per-gallon costs soaring past $7 a gallon in parts of the state. An Assembly committee held two hearings last week, with another set for Thursday.

Under immediate consideration: a bill that would allow the state to set minimum levels of gasoline storage at California’s refineries. The intention: to balance supply and demand to prevent retail price spikes when a refinery temporarily shuts down for maintenance.

But a bigger issue goes well beyond mundane matters of gasoline storage. The Legislature faces a fundamental question of government philosophy: How deeply should the state manage and control an industry that faces steady decline due to the state’s own policies, an industry that sells a product that will remain essential to a smooth-functioning economy even as it fades away?

And it faces another question: If the state decides to go deep, will it prove itself capable? The answer carries enormous implications for the household budgets of millions of Californians who will continue to drive gasoline-powered cars for years to come.

California’s government has positioned itself as a global leader on environmental issues. The world is watching to see how its climate-first greenhouse gas policies work out. Newsom has mandated that by 2035, carmakers and dealers can no longer sell new gasoline-only vehicles in California.

But even presuming the mandate stays in place, millions of gasoline-powered vehicles will remain on highways for decades.

So the state government is in a pickle. It wants to keep gasoline prices reasonably low, while state refineries, with no light at the end of their tunnel, want to pull in all the cash they can before their business disappears. If refineries cut back operations or close, or if their supply chains are disrupted, demand might exceed supply and drive up overall prices.

“As demand for gasoline declines, the industry will become more concentrated and potentially less competitive,” the California Energy Commission said in a recent report.

Newsom’s solution is heavier state intervention. The gasoline storage mandate is only the beginning. The recently created Division of Petroleum Market Oversight is ironing out details of a plan to financially penalize refineries that exceed a state-set profit margin that’s yet to be determined, and is investigating the opaque machinations of the spot market for petroleum products.

The California Energy Commission, meantime, has offered a list of 12 options for policymakers to help manage the industry decline while keeping gasoline prices stable and supply levels high.

Beyond a minimum inventory mandate for gasoline storage, the possibilities include a limit on retail gasoline profit margins; a state lease or ownership of storage tanks and the gasoline that would fill them; a state lease or ownership of oceangoing tankers that hold emergency supplies of gasoline; and even a state takeover of one or more gasoline refineries.

“The State of California would purchase and own refineries in the State to manage the supply and price of gasoline,” reads a report issued in draft version in May by the Energy Commission.

The industry, unsurprisingly, is not pleased. The main complaint: State managers can’t grasp the complexities of the gasoline production and supply system, and what’s seen as outside interference could increase prices if the system is made less efficient. Plus, they complain, over the decades, state taxes and mandates have been a prime cause of high gasoline prices in California.

“We are walking and walking and inching toward the Energy Commission … managing these refineries,” Eloy Garcia, a lobbyist for the Western States Petroleum Assn., told legislators. “We heard [at the hearing] that they are going to help us engineer the refinery. We heard they are going to tell us when to do maintenance. They’re going to tell us how much more supply, how to configure our tanks.”

Assemblymember Steve Bennett (D-Ventura) defended deeper state involvement while acknowledging that refineries are businesses driven by profits: “While I recognize that the industry has an obligation to maximize profits, we have an obligation also to maximize what’s in the interests of the public.”

Tai Milder, the government antitrust lawyer who heads the new petroleum market oversight division, said: “We want a well functioning market, but with regulations that incentivize the right conduct.”

Energy Commission Vice Chair Siva Gunda said California isn’t trying to dictate refinery logistics. “I think it’ll be a partnership with the industry. I think it’ll be a partnership with the Legislature, to think through how do we optimize the existing amount of storage we have.”

Gunda assured members of the Assembly’s special session committee on gasoline supply that refineries in California have plenty of room in their existing tanks to keep supplies from falling below 15 days’ worth.

State data show that when a refinery shuts down for maintenance, planned or unplanned, prices surge, at least in part because there’s not as much gasoline to go around. Retailers and refiners haul in extra profits as a result.

But Gunda added that he was speaking about aggregate storage capacity for all refiners, and that some refineries are squeezed tight. To manage that imbalance, he said, the state and refinery companies could work together on ways to share gasoline supply. He offered no details, but one prominent energy expert told the committee that the state might set up a trading system to help full-tanked refiners meet the state mandate. “It would require a careful design,” said Severin Borenstein, who heads the Energy Institute at UC Berkeley’s Haas School of Business.

In addition to any trading mechanism, Borenstein said, “we need to determine the size of the inventory, the timing and mechanism for release and for refill. We also need to determine the process by which release of those inventories could occur.”

He also warned that excess storage levels would be subject to “political manipulation” — for example, potentially allowing “whoever has political power to try to release that inventory when it is helpful for them to push down gasoline prices.”

Most members of the ad hoc Assembly Petroleum and Gasoline Supply Committee were noncommittal on the storage issue. The general consensus: The issue is complicated, and more information is required, including effects of state intervention on the state’s workforce and economy. The oil and gas business directly provides 100,000 jobs and comprises 5% of the state’s total economy, 10% if indirect jobs and businesses are considered, according to hearing testimony.

“This is certainly a dense and complicated issue,” Committee Chair Cottie Petrie-Norris (D-Irvine) said at the hearing. “It’s also one of utmost importance to 40 million Californians.”

More hearings, and plenty of debate, lie ahead.