As a huge Superman fan, I have long wanted to own Action Comics No. 419, the issue published in 1972 with an iconic cover showing the Man of Steel hurtling into the sky, seeming to fly right off the page. That’s why, earlier this year, I was delighted to finally track down a copy in the secondhand section of my local comic shop.

But I quickly discovered that this comic has another claim to fame. Within its pages, Superman became involved in one of the most significant chapters in the history of space science.

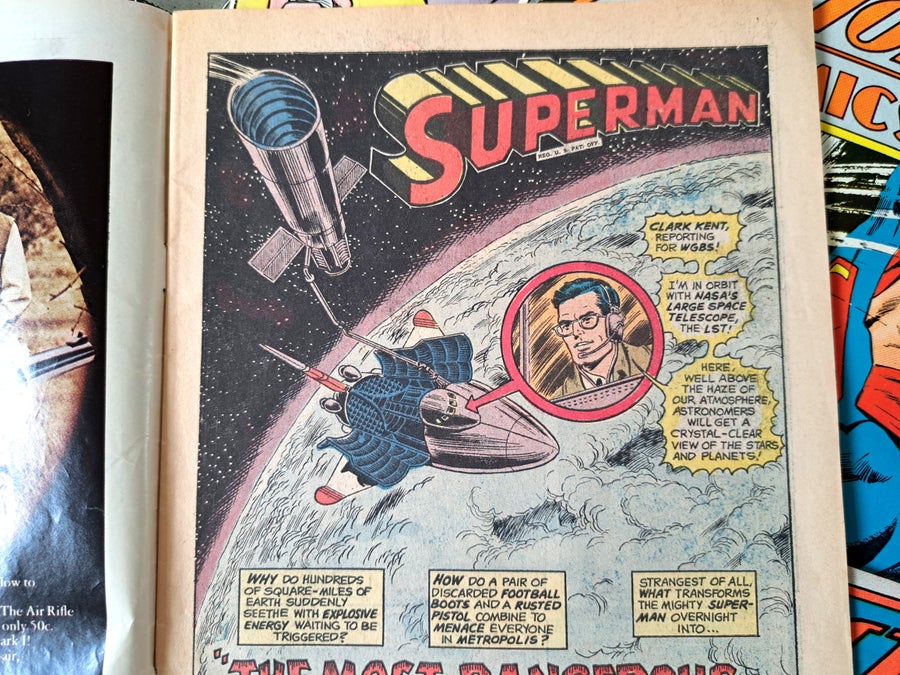

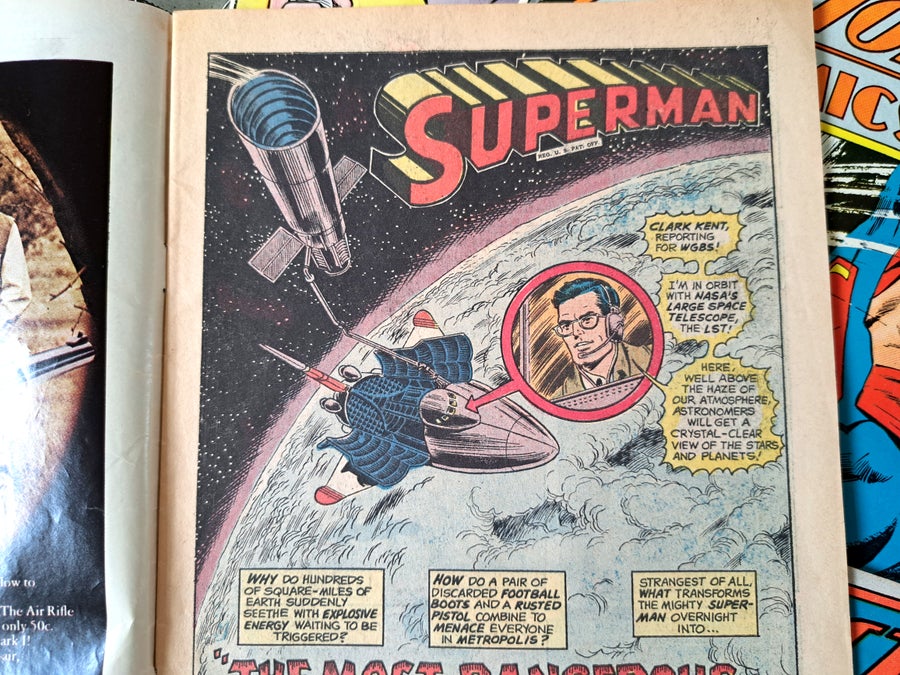

On the first page, reporter Clark Kent, Superman’s alter ego, covers the launch of a new NASA satellite while onboard a space shuttle. “I’m in orbit with NASA’s Large Space Telescope, the LST. Here, well above the haze of our atmosphere, astronomers will get a crystal-clear view of the stars and planets,” Kent says in the comic.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Right there on the page was a dead ringer for the real-life Hubble Space Telescope. I was baffled: How did the cartoon version of a space telescope that launched in 1990 get into a comic published in 1972?

On the first page of Action Comics No. 419, Superman visits the Large Space Telescope.

There was a clue in the story’s credits. Pete Simmons, then director of space astronomy at Grumman Aerospace Corporation (now Northrop Grumman), is credited with “technical assistance.” This was enough information for a Google search, which turned up a documentary clip from 1997.

What I learned amazed me. The Large Space Telescope was Hubble. While the project was named after astronomer Edwin Hubble in 1983, NASA had been developing plans for what it called a Large Space Telescope since the late 1960s. The agency had successfully launched its first successful space telescope, the Orbiting Astronomical Observatory 2 (OAO-2), in 1968, and by 1971 it had begun to conduct feasibility studies for a larger instrument to peer deeper into the cosmos.

But such an expensive project would be a tough sell in Congress. Simmons, who had previously worked on the OAO-2, took on the challenge of demonstrating to the public—and to Congress—that the LST was a worthy scientific investment. One day Simmons was on a plane to New York City when he noticed a child in the seat next to him reading a Superman comic, he recalled in an episode of the documentary series People Near Here, produced by Mountain Lake PBS.

“I thought, ‘Gee, those are pretty popular,’” he said in the documentary. He invited employees of DC Comics to the Grumman labs and showed them models of the LST, which convinced them that they should feature the telescope in a Superman story. The result was Action Comics No. 419. The comic sold well, as Superman comics usually did, giving Simmons tangible evidence of the American public’s interest in the LST that he could share with Congress.

“I went down to Washington, [D.C.]…, and we gave every member of Congress a copy of this Superman comic,” he recalled. “I remember asking as many as I could find…, ‘If I can get the Large Space Telescope talked about in Superman comics, would you think it’s popular enough…?’ Then I’d give them a copy of this issue.”

I needed to know more. My two great interests—comic books and space science—were colliding. Could we really have Superman to thank for all the important discoveries and stunning images made by the Hubble Space Telescope?

Sadly, Simmons died in 2018. So I contacted Charles Robert O’Dell, an observational astronomer and lead scientist on the Large Space Telescope project from 1972 to 1983.

O’Dell told me that in the early days of the project, the fate of the LST was not solely in the hands of Congress. Proponents also had to convince their fellow astronomers, many of whom would have preferred the money be spent on Earth-based telescopes, that the LST was a worthy investment.

“We organized what we called ‘dog and pony shows’ of NASA engineers and managers,” he says. “[We] went to [Harvard University, the University of Chicago and the California Institute of Technology] and spoke at those places, proselytizing the LST. And this did sway people.”

But in the eyes of astronomers, Action Comics No. 419 wasn’t exactly a selling point for the LST. “In fact, it was a turnoff,” O’Dell says. “Remember how conservative astronomy was as a body at that time…. And so, seeing a comic—it was just an alien concept.”

To convince Congress, O’Dell believes that the comic would only really have been useful in the hands of a natural salesperson like Simmons. “[Simmons] would go in with this enormous salesman’s enthusiasm for the project and pull that comic out…. He could pull something like that off,” O’Dell says.

O’Dell can’t confirm how much influence the comic had on Congress. And the telescope still had a tough fight for funding ahead. In 1974 and 1976 astronomers undertook campaigns to lobby support for the project in Congress. They sent letters and telegrams and even made personal visits to Capitol Hill.

In 1977 the legislature finally approved funding of the LST. Thirteen years later, under a new name, the Hubble Space Telescope was launched. It has been operating for more than three decades, and it was the first observatory to detect elements from the early universe, image the surface of a star besides the sun and confirm the presence of supermassive black holes. And it owes its existence, I learned, more to the hard work and passion of people like O’Dell and Simmons than to any fictional superhero.

But somehow I think Superman would prefer it that way.