This article is taken from the December-January 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

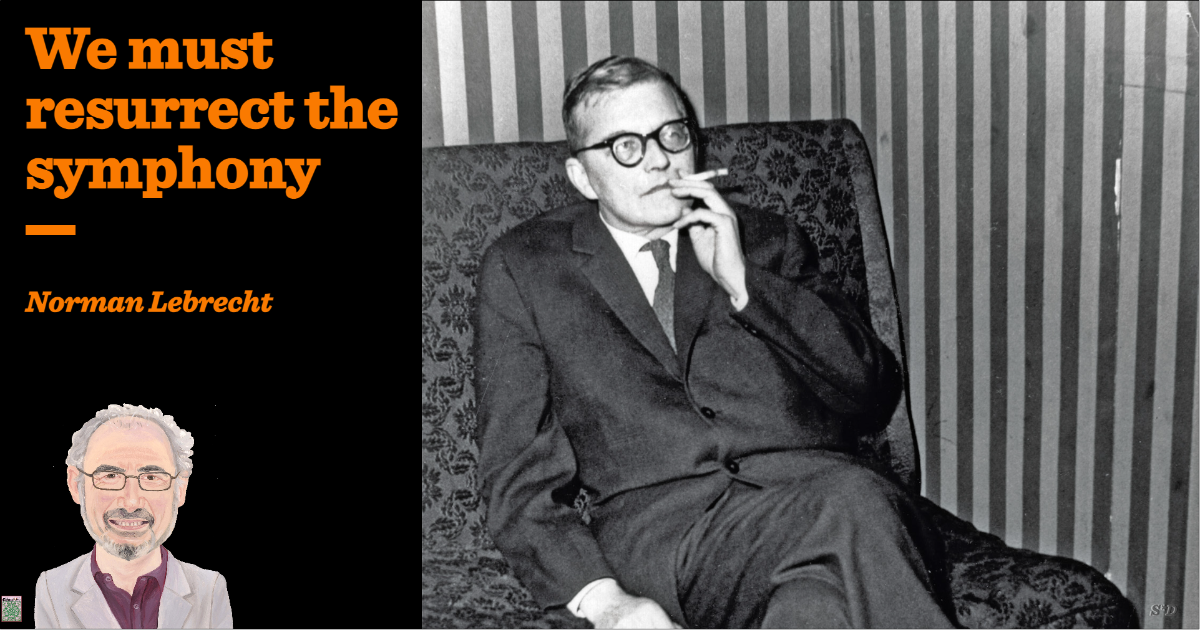

I remember well the day the symphony died. It was August 1975, and I was sitting in a television newsroom when the teleprinter clattered out a Moscow dateline. “Hold the bulletin,” I cried. “Shostakovich is dead.”

I was met by a wall of blank faces. “The greatest Russian composer since Tchaikovsky?” I tried. They’d heard of Tchaikovsky. “The Leningrad Symphony?” Not a flicker.

My colleagues were world-travelled reporters and editors, well-read in modern history. Yet not one of them went to symphony concerts or took an interest in an art form that had been running about the same length of time as the United States of America.

The USA commanded our constant professional attention. The symphony was peripheral. That day, 50 summers ago, I realised the symphony was dead.

Turns out, I wasn’t wrong. Since the last gasp of Dmitri Shostakovich, not one symphony has changed the world or enlarged the concert repertoire.

There was a flash of headlines for Henryk Górecki’s Polish Symphony of Sorrowful Songs and another for John Corigliano’s patchwork symphony for Aids victims, but these flatteries proved ephemeral. Neither contemporary work has joined a canon which was shut down in 1975.

Symphonies by major names — Philip Glass, Arvo Pärt — came and went, even though Glass based three symphonies on David Bowie albums and Pärt foretold the collapse of the Soviet Union. A masterful third symphony by Witold Lutosławski, written amidst the risings in Gdansk, marked its own time without accruing immortality.

The symphony had simply disconnected. Gone were the days when families clustered around the living-room wireless, awaiting an oracular seventh symphony by Shostakovich, the fifth of Vaughan Williams, the never-to-be eighth of Jean Sibelius.

Shostakovich, in his fifteenth and final symphony, left some pages near-blank, as if the notes had drained out through a sieve. In his sixties, exhausted, Shostakovich took the canon with him to the grave.

A furore followed. In 1979, a book purporting to be Shostakovich’s memoirs, brought out by the journalist Solomon Volkov, was published in America. It reimaged the composer as a brave critic of communism, embedding his scores with dual meanings — a fixed smile for party chiefs and a sympathetic wince for fellow-sufferers.

Ambiguity, Gustav Mahler’s musical invention, was reworked by Shostakovich as political commentary. His fifth symphony, delivered in fake humility as “a Soviet artist’s response to just criticism”, conveyed Stalin’s Terror so graphically, it is a wonder the Kremlin was fooled.

Volkov’s portrait of the composer, if not his every word, was endorsed by the cellist Mstislav Rostropovich. Maxim Shostakovich, the composer’s son who defected to the West in 1981, confirmed that his father used the symphony as a witness to history. The Kremlin, rattled, paraded a row of cultural stooges who swore that Shostakovich was a loyal Soviet citizen.

Then it got ugly. A blustering American academic, Richard Taruskin, demanded that Volkov produce pages of manuscript initialled “DSCH”, the acronym Shostakovich used as his musical signature. This was preposterous.

I called out Taruskin as a David Irving-like revisionist, refusing to believe Hitler initiated the Holocaust unless he saw a signed order. Whilst Taruskin acolytes controlled the university presses, Volkov won the media debate, with backing from Vladimir Ashkenazy, Rudolf Barshai, Kirill Kondrashin and other exiles.

In the concert hall, a third way emerged. The Leningrad conductors Yevgeny Mravinsky and Kurt Sanderling, who had first sight of the symphonies, steered a zigzag line. Sanderling confided to Western orchestras that a trombone solo in the eighth symphony depicted a pompous party official on a foreign mission; a piccolo was a soldier on a weekend furlough with his girl. Attending Sanderling’s rehearsals, I understood a Shostakovich symphony as a caricature-filled Charles Dickens novel, a Soviet-styled Sketches by Boz.

Others, like the Dutch maestro, Bernard Haitink, approached Shostakovich as pure music, no added context. Haitink’s tremendous account of the fourth symphony at the 2008 BBC Proms was at once redemptive and troubling, demonstrating that music could mean anything you want, or nothing at all.

What would a Martian make of this symphony, except that it was music? The Shostakovich schism muddied the public perception of what a symphony ought to be. Was it an abstract construct, a coded communication or a cultural obligation? Confusion ensued.

The original symphony was intended as relief from reality. Joseph Haydn wrote dance moves. Mozart added tonal diversity. Beethoven reached for apotheosis, Brahms offered reassurance, Tchaikovsky sought catharsis, Bruckner divine affirmation, Mahler self-analysis, Sibelius icy clarity. Their achievements will be treasured so long as society is prepared to pay for 50 to 150 musicians to perform them.

But society has sped up and fewer listeners are prepared to wait an hour or more for a resolution of a work that may, or may not, meet their personal needs. The symphony, post-Shostakovich, is stuck in a minefield with no clear way out. Without it, though, the concert is doomed. The concert is a prix-fixe menu with symphony as main course. Take out the symphony, and the restaurant will have to shut. The need for renewal is existential.

Orchestras, to survive, must refresh the palate with unfancied modernities — Henze’s 7th, Penderecki’s 8th, Maxwell Davies’ 9th, Rautavaara’s 8th, Schnittke’s last three.

Concert halls need to commission young symphonists in the way that enterprising opera houses are engaging with new writers. The symphony may be dead, but it is not beyond resurrection. All it requires is a declaration of faith in the form to revive public attention. There is no alternative, and no time to waste. Without new symphonies, orchestras will die.