Horowitz remembers the Merwin transaction as a vital moment in his growth, but Merwin and his wife always believed, without any proof, that Horowitz had cherry-picked his library for his own benefit. A leading appraiser told me that Merwin repeatedly complained that Horowitz had shorted him on the payment for his archive. (Horowitz denied this, and said that he had bought at least fifty of Merwin’s books without incident.) Twenty years after the sale, M. G. Lord, who by then had become a writer herself, went to see Merwin read in Los Angeles. “I expected to be greeted warmly, but he wouldn’t speak to me,” she told me. “Paula took me aside and basically said, ‘You have to understand—Glenn stole from him. And we kind of hate you, because you were complicit.’ ”

Horowitz said that when his team catalogues an archive, “I ask myself, ‘How heavily biographied will this person be?’ I’m looking for correspondence with publishers and agents and editors and other writers, which can open up research in lots of directions. You yearn to find intimate documentation, diaries and journals, that has never been disclosed.” Yet archives, in one way or another, are invariably incomplete. Michael Ryan, a retired curator, said, “You’re always seeking the complete correspondence, but what you mostly wind up with are incoming letters. You can only get a piece of the man, not the full man.” Curators like an archive to “talk” to their other collections: it makes more sense to acquire the correspondence of Maxwell Perkins if you already have the other side of some of it from Hemingway or Fitzgerald.

Ultimately, though, what Horowitz is selling is a writer’s conversation with the culture at large. When he pitched David Mamet to Tom Staley, a longtime archival director at the University of Texas at Austin, he characterized him as “the last American playwright, somebody whose work, like that of Williams, Miller, and O’Neill, became part of the larger dialogue.” Sold, for $1.65 million!

Staley was a like-minded ally. He was determined to make his library, the Harry Ransom Center, the leading American repository for literary archives. Horowitz sold him some forty archives and collections, for about $25 million, and routinely used him as a sounding board and a stalking horse. To avoid cultural-repatriation laws, Staley had a trove of literary papers smuggled out of France in a bakery truck; to avoid apartheid-era sanctions, Horowitz had Nadine Gordimer’s archive shipped out of South Africa as a cargo of books. Both men loved a marquee name and a lavish deal that could be framed as a bargain. In 2005, when Norman Mailer was shopping his archive for $5 million, Horowitz told Staley that he was prepared to offer it for just $2.5 million. “And that’s the price at which I will buy it!” Staley replied.

Both men also relished a memorable story. Staley told Tony Kushner that when he visited Arthur Miller’s house he asked about a bundle of letters tied with pink ribbon, and Miller said, “Oh, those are from Marilyn,” and tossed them into the fireplace. Horowitz scoffed when I mentioned the anecdote, saying, “I drank enough Scotch with Tom late at night that if he’d watched Arthur Miller burn Marilyn Monroe’s letters I would have heard of it. Tom was a world-builder, a fabulist.” Tracey Jackson said of Staley, who died in 2022, “Tom was in many ways the father Glenn never had.”

Horowitz faced greater obstacles in constructing an actual family. By the mid-nineties, he and Lord were living apart. He said, “I felt that if an environment was created where M.G. felt loved and secure, this would somehow expunge her need to express her attraction toward women—but it doesn’t work that way, unfortunately.” They eventually agreed to divorce, and the proceedings became contentious. When Horowitz shipped Lord’s dishware to her in Los Angeles, she told me, “my mother’s plates, my grandmother’s Limoges—it was all sent with no packing material, so everything was in shards. He blamed it on his packer, but I’d seen how the packer carefully packs rare books, so I find it hard to believe it was accidental. Glenn can be very not nice, too.” Horowitz said, “I would never intentionally destroy her family heirlooms,” adding, “It may be part of the lack of empathy that people accuse me of, but I have no memory of it.”

Uniquely among major American dealers, Horowitz never became a full member of the A.B.A.A. It’s a point of pride for him. One reason he gives is that the association’s only real perk is the ability to exhibit at its rare-book fairs. He suggested another reason to the dealer Sunday Steinkirchner when she mentioned that she was applying for membership: “Why would you want to be bound by a code of ethics?” (Horowitz denied making the remark, adding, “Even if I felt that way, why would I say it?”)

Whatever his rationale, Horowitz was unsuited to the usual forms of collegiality. He can be magisterially slow to pay his peers. One dealer said, “After years of chasing him, I started putting on my invoices, ‘Due on X date, or the property must be returned.’ I don’t do that with anyone else.” A former assistant of Horowitz’s, Katie Vagnino, described a typical dodge: “If someone called and said, ‘I’m waiting for that payment,’ Glenn would say, ‘Tell them we mailed the check two days ago.’ ” (Horowitz said that he would settle any overlooked bills if a reminder came in.)

The dealer Joshua Mann told me, “The space Glenn wants to be in with you is negotiating, challenging you. The first time he bought from us, we had an atlas inscribed by Truman Capote to Perry Smith, one of the killers in ‘In Cold Blood.’ We asked seventy-five hundred dollars, and he bludgeoned us down to less than six thousand. Right afterward, he said, ‘I would have paid your price, but I wanted to see what I could get.’ ” Horowitz’s favorite approach with other dealers is to ask, “What’s the lowest price you could afford to sell it to me at?” When the dealer says, “Well, X, because that’s what I paid for it,” Horowitz replies, “That’s not true—you could afford to sell it for a dollar. You own it, right? It’s just sitting on your shelf gathering dust. Taking your losses is often very healthy!”

Most booksellers resist that everything-must-go framework because they remain collectors at heart. The dealer Michael DiRuggiero showed me a copy of Philip Pullman’s “The Amber Spyglass” that Pullman had inscribed with a detailed account of his creative process. “This is the copy of this book,” he said, “and I’m never selling it.” Horowitz rejects such views. He likes to say, “You succeed in business by moving product from point A to point B.” When writer friends such as Joseph Heller and James Salter inscribed books to Horowitz, those books often ended up for sale.

I spoke with three women who worked for Horowitz. They told me that he taught them to write crisp copy, to treat each book as a unique work of art, to read people, and to stand up for themselves. “Glenn made book recommendations, from ‘Housekeeping’ to ‘Wide Sargasso Sea,’ that opened up a world for me,” Jess Butterbaugh, who is now a project manager at Carnegie Mellon’s Robotics Institute, said. They also told me that he would ask if they wanted to borrow his credit card to buy nicer clothes, inquire about who they’d had sex with over the weekend, or, unprompted, give them weight-loss targets. (Horowitz denies this behavior.) In 1994, he interviewed Jessy Randall to be his cataloguer. She told me, “He asked, ‘Do you have a boyfriend?’ ‘Do you like to smoke marijuana?’ ‘Are you a lesbian?’ I finally said, ‘You know these questions are illegal, right?’—which I think might have gotten me the job. Glenn’s comfort zone was being in an adversarial relationship with everyone.” Katie Vagnino told me that once, when Horowitz got mad at her, he e-mailed her a “Bond villain-esque” warning: “You are standing on such a thin sheet of ice you can’t even begin to see how far you can fall.”

Several of Horowitz’s younger colleagues told me that he can be generous with his time and his knowledge. Amir Naghib said, “When my wife came down with long Covid and my daughter was sick for more than a month, I heard from Glenn twice a day, asking what he could do to help.” But the dealer’s acquisitive focus often operated as a Midas touch, turning those around him into golden objects. A collector named Richard Levey told me that he did business with Horowitz for more than fifteen years, beginning in the eighties. Horowitz sent him items from Robert Lowell and his circle, and Levey sent back Joyce, Huxley, Eliot, and Marianne Moore. “Glenn stayed at my house in Detroit, inquired sincerely about everyone’s health, and stank up the place with his cigars,” Levey said. “We were friends. We even published a small book together. But, other than one check for twenty-five thousand dollars for a ‘Ulysses,’ I don’t remember getting any money from him. Every time I asked to see a statement of what he owed me, he’d just send me another bill for what I owed him. All in all, I think I’m at least a hundred thousand dollars poorer than I should be.” (Horowitz maintains that Levey’s figures are “just the memory of an older man,” and that, if anything, Levey probably owes him money.) Levey, who didn’t keep documentation of his side of the bartering, acknowledges that a less absent-minded customer would have demanded clearer accounting. “Had my eyes been a little smaller, things would have turned out differently,” he said. “But every time I’d start to question Glenn he’d say, ‘Boy, have I got something for you!’ ”

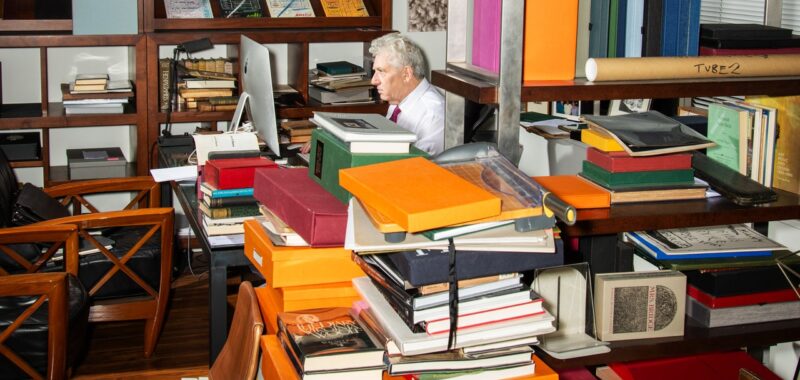

One morning, I met Horowitz at Christie’s Fine Art Storage Services, an air-conditioned warehouse near the Red Hook waterfront. Eight boxes sat on a table in an otherwise empty room: a Joyce collection, much of it purchased from Horowitz, whose owner had decided to sell. “This is the best Joyce collection in private hands,” Horowitz said. “Admittedly, there is not usually any satisfaction for the collector in getting the books all at once. However,” he went on, his eyes gleaming as he opened a box, “this is a unique opportunity for a family in the U.A.E. or for a library in Canada or Japan . . .” He trailed off, nonplussed to find that the books were all wrapped in white Tyvek, a generic department-store display. He phoned and asked his assistant Silas Oliveira to join him. As Oliveira held bundles aloft, Horowitz shook his head and said, “Nah, that’s nothing . . . Nothing . . . Of no consequence.” He clarified: “The ‘Ulysses’ we’re looking for, the ones printed in Paris by Sylvia Beach, will be two and a half times that size.”

When Oliveira finally supplied the book he’d most been awaiting, he examined the inscription, angled on the title page in Joyce’s bold hand: “To Ezra Pound: In token of gratitude.” His face turned a delicate pink. “Despite the surfeit of great books I’ve been blessed to handle,” he said, “there’s something electrifying, a powerful gas released into the atmosphere, about getting your hands on this copy.” Flipping through the pages, he said, “Pound helped edit ‘Ulysses,’ as well as ‘The Waste Land,’ the twin modernist masterpieces, right at this time. Pound knew everything, one of the half-dozen great brains. He knew French and some Chinese and, in his own meshugganah way, economics.”

He thought that the book, which he’d first bought from Pound’s daughter in the late nineties for a six-figure sum, could now be worth $3 million, if he could stimulate a buyer’s appetite. Horowitz’s erudition, combined with his energy, is a powerful sales tool. He has a nose for people with income to dispose of and no notion of how it should be disposed. “You want someone who is educable,” he told me. He sometimes referred to his bookshop in East Hampton as “the butterfly net”: it drew in window shoppers, such as Martha Stewart, whom Horowitz would turn into industrious collectors.

In the early eighties, Dennis Silverman, the president of a Teamsters Union chapter, came to Horowitz asking about pulp fiction by Mickey Spillane and H. P. Lovecraft. Horowitz elevated his attention to James Joyce. The Teamster was daunted by Joyce’s prose, but not by the requisite investment. “That fucking ‘Ulysses’!” he said. “I decided I’d just buy the books.”

Among his prizes was a “Ulysses” inscribed by Joyce to a book scout named Henry Kaeser, which Horowitz sold him for $48,500. But the book didn’t stay Silverman’s for long. He was subsequently forced from the union for embezzlement, and, as Horowitz told me, “Dennis, alas, died an alcoholic with an ankle bracelet on his foot, needing money.” Horowitz bought the Kaeser copy back, along with the rest of his client’s collection, and then sold it, for $115,000, to Roger Rechler, a Long Island real-estate developer whom he described to a colleague as the kind of man “who walks on his knuckles.”