[ad_1]

November 21, 2024

5 min read

New Bird Flu Cases in Young People Are Raising Concerns about Mutating Virus

Canada’s first human case of bird flu has left a teenager in critical condition as human infections continue to emerge in the western U.S.

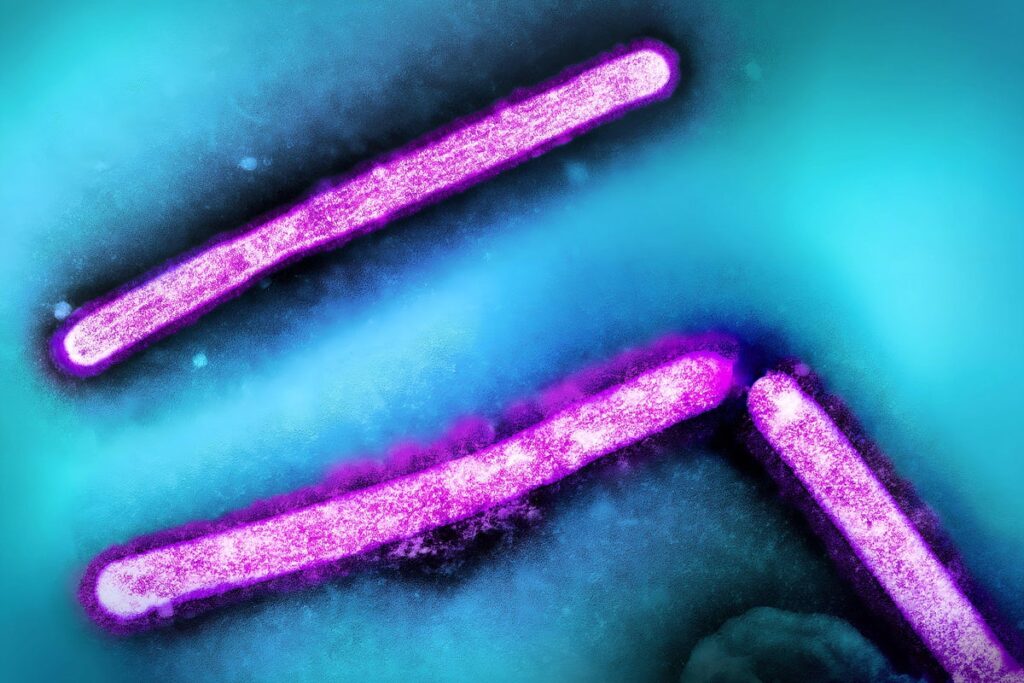

Three influenza A H5N1/bird flu virus particles. Layout incorporates two CDC transmission electron micrographs that have been repositioned and colorized by NIAID.

Imago/NIH-NIAID/Image Point FR/BSIP/Alamy Stock Photo

Since a strain of avian influenza was first detected in U.S. dairy cows this past spring, it has caused relatively mild illness in humans, with most cases seen in farmworkers who were directly exposed to sick dairy cows or poultry. But two unusual cases in children who had no known prior contact with infected animals are increasing scientists’ concerns that the infections foreshadow a larger public health threat. On Tuesday a child in California with a mild infection tested positive for low levels of a bird flu virus that is most likely H5N1. And Canadian health officials announced last week that a teenager in British Columbia who was hospitalized with bird flu was in critical condition—the country’s first locally acquired infection.

“We’re not containing the outbreak,” says Seema Lakdawala, an associate professor of microbiology and immunology at the Emory University School of Medicine. “Most likely this British Columbian case is not going to be the only time a kid is hospitalized with H5N1.”

In both cases, family members and close contacts have tested negative for the virus, and officials report no evidence of person-to-person transmission. The Canadian teen, whose age and sex have been withheld, initially had symptoms similar to other cases reported so far: fever, coughing and conjunctivitis—an eye infection that’s been common with bird flu. The teen later developed acute respiratory distress, however, despite having no underlying health issues. A person in Missouri with a history of chronic respiratory illness tested positive for bird flu while hospitalized for gastrointestinal symptoms in September.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has logged 52 bird flu cases in people since April 2024. But experts suspect this is likely an undercount. A recent CDC study of 115 dairy workers exposed to infected cows found 7 percent of them had antibodies for H5N1 even though half of those didn’t report any symptoms.

Though the study was conducted with a relatively small sample of farmworkers, what it “highlights for us is that we are obviously underestimating the number of human infections,” Lakdawala says. “A lot of infections that are maybe asymptomatic or quite mild don’t always produce a strong antibody response,” which could mean the study’s antibody test may have missed some cases.

Scientific American spoke with influenza experts about recent bird flu cases in humans, preliminary genetic information and the risk of exposure and infection.

Animal Spillovers

The strain of H5N1 currently circulating in North America was mostly contained to wild migratory birds before it started to spill over around 2022 into other animal populations, such as minks, bears, foxes and marine mammals. Currently in the U.S. the virus has largely been affecting dairy cows and poultry.

“I think what’s really changed since this particular strain emerged is its somewhat unique ability to cross over and infect a lot of different mammals,” says Stacey Schultz-Cherry, who studies the ecology of influenza in animals and birds at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. “There have been reports quite a long time ago of occasional spillover, but nothing quite like we’re seeing now.”

H5N1 can be very deadly in poultry, whereas cows usually recover from their symptoms, which include fever, dehydration and abnormal milk production. The variety of animals plagued by H5N1 so far poses a problem in tracing sources of human infection, Lakdawala says.

Source Tracing Troubles

Investigations are currently underway to identify the sources of infection for the child in California and the teen in Canada. Neither reported any known recent exposure to sick wild or farm animals or pets. A Canadian health official said in a press conference on November 12 that it’s a “very real possibility” investigators will never be able to confirm the source. A sick wild bird may not show any symptoms, for instance, Schultz-Cherry says.

Genetic sequencing of emerging strains is offering some clues. Test results of the strain that caused illness in the teen suggests it is similar to the one currently circulating in poultry in Canada. Some scientists flagged a specific mutation in the sequence that’s known to be important for altering the virus’s receptor preference—possibly allowing it to bind more readily to human cells. A genetic change associated with viral adaptation to mammals was seen in the analysis of another recent human case in Texas, Lakdawala says. “What this means is that the virus is adapting to humans to gain mammalian genetic signatures,” she suggests. “We need to stop the amount of H5N1 in animal species, particularly in cattle and poultry farms, to reduce the amount of possible exposures and spillovers into humans. This will prevent the virus from taking so many shots on goal to reach an optimal mammalian fitness.”

Bird flu remains a relatively low risk for most people, but those who work directly with sick dairy cows or poultry are at higher risk. Sustained person-to-person transmission of H5N1 hasn’t been observed, but Schultz-Cherry says it’s important to closely monitor the virus for any genetic changes that would allow it to gain that ability or cause increased disease severity.

Understanding Severe Infection

In previous outbreaks, H5N1 has caused severe disease and occasionally death in people, Schultz-Cherry says. With the exception of the hospitalized teen, “we’ve been very lucky that these events have been [mostly] mild, but it is a bit different than what we had seen historically, and we don’t know why.” Canadian health officials suggested that the teenager’s critical condition may hint that the virus could be more severe in younger age groups. But the ages of the young people with recent cases—and most of the human bird flu cases this year—haven’t been made public, which further complicates experts’ ability to understand the risk of severe disease.

Lakdawala’s team has investigated the role of preexisting immunity—protection developed from past infections such as seasonal flu—on H5N1 disease progression. The findings, which are currently under peer review, suggest older people may have more antibody cross-reactivity—the ability of antibodies that are originally primed to seasonal influenza to also respond to H5N1—compared with younger individuals. That could be because younger children haven’t encountered flu infections such as these before, Lakdawala explains. “Our immune responses are going to see [a virus] differently based on our prior immunity,” she says, but adds, “I don’t know what this [Canadian] individual’s prior immunity was like.” Schultz-Cherry and Lakdawala say it’s too early to draw any conclusions with such limited data and information.

There are several tactics people and farmworkers with high risk of exposure in particular can take to lower their risk of infection. Washing hands, disinfecting surfaces—including milking and farming equipment—and using protective gear can help. People in general should keep themselves—and their pets—away from dead wild birds or animals and avoid consuming raw milk and raw cheeses. Getting a seasonal flu vaccine is also particularly important this year, Schultz-Cherry says. “We want to do everything possible to avoid giving [the H5N1 virus] an opportunity to reassort” in a person or animal infected with seasonal flu, she says. “Could they actually share genetic material and cause a new virus to emerge? I think that’s the biggest concern as we move into the human seasonal influenza time.”

[ad_2]

Source link