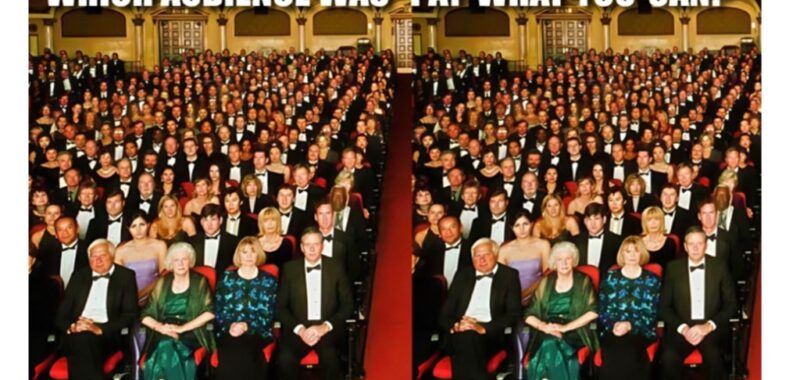

The well-intentioned, ghettoized program asks us: are Abe and Sophie still the ones coming, only now they’re paying less?

An elderly couple in Florida are going out to dinner. Abe’s at the door, but Sophie’s still upstairs in the bedroom.

Abe: Hurry up, Darling!

Sophie: I’m coming, Sweetheart! I just have to put on my 18-inch, double-strand pearls!

Abe: Hurry up, Darling!

Sophie: I’m coming, Sweetheart! I just have to put on my 40-karat diamond ring!

Abe: Hurry up, Darling!

Sophie: I’m coming, Sweetheart! I just have to put on my full-length mink!

Abe: Would you hurry up already?! We’re going to miss the early-bird special!

Nonprofit performing arts organizations have been presenting “Pay-What-You-Can” (PWYC or Pay-What-You-Will, Pay-What-You-Want, Pay-What-You-Choose, and other monikers) for years now. It’s a pretty cheap way to deal with a lousy-selling night of the week (they always seem to fall on Tuesday nights or midweek matinees, or often, in the theater world, final dress rehearsals) and look like you care for your community at the same time.

In the museum world, the practice is usually called something like “First Thursday,” and offers free admission for a certain time period during a Thursday, when attendance lags anyway. It’s a little different from PWYC, in that museums sometimes offer talks or tours free of charge for those events as well.

When PWYC’s proponents offer one performance at whatever the audience member wishes to pay, they believe they are reaching out to a community of people for whom price is the only obstacle to attendance and fandom. And they claim, with questionable data gathering techniques such as lists of names of attendees and no follow-up, that each event is predominately comprised of “first-timers,” those whose names had not appeared on their lists before that performance. They see it as community service, proof that they care, really care, REALLY REALLY care about the community, which they define as “their audience.”

Bushwa.

PWYC is cheap, easy, and sounds productive. It’s also outdated and offers little in the way of audience development, proof of worth as a nonprofit, or even first-time event-going. The risk is negligible — the performance was probably a lightly-sold one in the first place. As a result, PWYC offers little reward except to add a small rubber-stamped paragraph to a grant application and make a few insiders feel better. But at what cost?

After 30 years of working with PWYC performances, I can honestly say that a number of people in the audience would actually pay the price for a ticket but, like the coupon-clipping Abe and Sophies of the world, just want to save a buck. Aside from them, you’ll find volunteer ushers, seniors who used to attend, and a few people for whom that’s just the night that works best for them.

There’s nothing inherently wrong about appealing to any of these groups, but it’s not audience development nor is it community service. PWYC performances still force people for whom money is an issue to travel to a venue, often causing unwanted expenses elsewhere (parking, etc.). They do not occur, in general, in the neighborhoods of people who need help or who, at the very least, might diversify the audience base. God forbid.

Finally, it reeks of good master plantation behavior. “Come on in from the hot fields and horrible working conditions and have dinner inside the house for one night,” they seem to be telling the community. After the performance, they’re sent back. Then, in today’s world, their names are put on mailing lists which are sold, traded, and otherwise leaked, and they’re asked to donate at every possible opportunity, even though money and lack of same were interpreted by that same arts organization to be motivators for presenting a PWYC performance in the first place.

I often tell the story of attending a midweek matinee PWYC at Seattle Rep in the late 1990s and running into Bill Gates. Literally. As in, we were each running after our respective partners at the end of intermission and crashed into each other, nearly knocking us on our respective tuchuses. Both of us laughed and apologized and continued our pursuits. Then, one thought stopped me: this was a Pay-What-You-Can performance. Bill Gates can pay a million dollars for a ticket. I always wondered whether he did.

Now we get to the crux of the question that motivated PWYC performances in the first place. Why do them?

If there were no advantage to pursuing a program to aid those in need, would your local behemoth nonprofit arts organization engage in it?

After all, PWYC is just one program that shows nicely on a grant application. But if it didn’t, or if that organization just had some free performances (plural) at which people with little means could attend that were just done because it’s the right thing to do, would these same organizations do them? If free tickets at any performance were utilized not as an audience development tactic (the wrongheaded thinking being that a $5 ticket suddenly transforms into a $100 ticket for the second moment of attendance), but as a gift to those who get always seem to get the fuzzy end of the lollipop, would it be the wrong thing to do?

There are ways of offering service to those in your community who need help. PWYC is not one of them. Why not try some of these?

If you insist on hosting people at your venue — which is the worst way to diversify your audience base and help your community, but stubbornness is a hallmark of toxic nonprofit arts organizations) — then, instead of partitioning off one performance, offer free tickets (not as audience development, but as community help) to all your performances based on who the person is, not who you are. Cater to their convenience, not yours. For example, honoring elementary educators with free tickets might be a caring, community-minded thing to do; but they work hard all week, go to bed early to get there before the kids, and are only available (for the most part) for weekend performances.

Don’t make them come to a Tuesday night just because you can’t sell tickets to a Tuesday night. Wouldn’t you be better off inviting them and letting them come to a Saturday night because that’s more convenient for them?

Can they buy their tickets in advance? If not, why not?

Is your nonprofit arts organization looking after their needs before your own? “Service Above Self” isn’t just the Rotary Club motto; it should guide everything every nonprofit does.

What about groups of people whose live in insecurity and horror? Would you offer free tickets to people at a domestic abuse shelter, who could really use a break? Afterwards, would you refrain from talking about it, even on a grant application, so that their fear of being traced by their abusers can be mitigated? Or do you only do community service when there’s money involved?

What about ex-cons living in halfway houses — those who have completely served their time but can’t get work because of that checkbox on the application form? Can’t they get a night out?

Or does your organization believe that their attendance at your cultured event would negatively affect the elite folks that attend now?

If that’s the case, you might have bigger systemic problems than a silly PWYC performance.

Related